RCEP Could Limit Access to Medicines

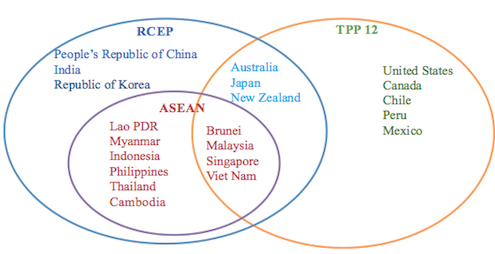

As opposition to the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement intensifies in the United States and Japan, Australia is presently hosting negotiations for another regional trade agreement which is raising serious concerns for worldwide access to medicines. Negotiators for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement (RCEP) are currently in Perth this week for their twelfth round of negotiations. RCEP is under negotiation between the ten ASEAN member states and the six countries that have existing trade agreements with ASEAN; Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, China and South Korea. Like the TPP, RCEP goes beyond trade in goods to cover services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, electronic commerce, competition, dispute settlement, and intellectual property.

High levels of intellectual property protection can delay the market entry of generics, creating problems for access to medicines if monopoly drugs are priced out of reach for those who need them. Public health advocates have demonstrated, for example, that Vietnam’s treatment coverage for people living with HIV/AIDS could drop to merely thirty per cent of the population in need if Vietnam adopted a level of IP protection often sought by the United States in its trade agreements.

The RCEP negotiations did not initially present a red flag for public health as the agreement was framed as an attempt to maintain “ASEAN centrality” in the region, notably excluding the United States while including India and China who are not party to the TPP. However, draft intellectual property chapters proposed by Japan and South Korea, leaked online last year, signalled that high of levels of intellectual property protection are being sought in RCEP.

A consolidated intellectual property chapter draft for RCEP, dated 15 October 2015, was leaked online this week. The text contains IP measures that go beyond multilateral trade agreements which could delay the entry of generic medicines in several low and middle income RCEP countries, with broader implications for countries that import generics from countries like India.

One provision in the recent leaked IP chapter would require governments to provide patent term extensions to compensate for ‘delays’ in the marketing approval process. This would extend the period of a patent monopoly, further delaying the entry of generics. A 2008 study of the potential impact of five year patent term extensions in Thailand found that the economic impact would be US$821 million after five years and over six billion dollars over twenty years. An independent Pharmaceutical Patent Review panel in Australia found that the Australian government, which currently provides for five year patent term extensions, would save up to AUS$244 million a year if patent terms extensions were eliminated.

Another IP provision in the RCEP draft IP text is data exclusivity. This mechanism is separate to the patent system and prevents a generic manufacturer from citing an originator’s clinical test data in their marketing application until the exclusivity period has expired. A study of the impact of data exclusivity measures introduced by Jordan in 2001 found ‘significant delays’ to the generic entry of seventy-nine percent of medicines examined and concluded that generic entry would have reduced drug costs by US$6.3 – 22.05 million in the study period. Similarly, a 2008 Thai study found that five years data exclusivity could introduce US$2,400 million in extra costs after five years (from 2008 baseline data). In Australia, which currently provides for data protection, an independent Pharmaceutical Patent Review panel found that data protection has had ‘little impact on the levels of pharmaceutical investment in the country’, the claimed rationale for providing extra protection.

Low and middle income RCEP countries that are not party to the TPP include India, China, Indonesia, Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, and Laos. These countries have large populations and economic pressures on the availability and affordability of medicines. High levels of IP protection in RCEP could constrain their capacity to provide affordable medicines to their populations. This would likely have implications beyond RCEP as India exports pharmaceuticals to more than two hundred countries and produces eighty per cent of the world’s supply of generic HIV/AIDS medicines. While some RCEP countries like Australia already have higher levels of IP in their domestic patent laws, agreeing to these provisions in RCEP would constrain future patent law reform.

According to UNAIDS, more than half the people eligible for HIV treatment in the Pacific region do not have access and affordability remains a key factor. In addition to calling on countries to make use of flexibilities in multilateral IP agreements to protect public health, UNAIDS has called for “closer collaboration between the trade and health sectors so that trade agreements will not hinder access to affordable medicines.”

The RCEP IP leaks raise concerns for access to medicines in low and middle income RCEP countries and beyond. High levels of IP should be resisted in RCEP in order to prevent further barriers to affordable access to medicines in the region.

Belinda Townsend is a member of the Public Health Association of Australia and the People’s Health Movement. She has written several papers on the TPP, RCEP and public health issues. She can be reached at bel.townsend@deakin.edu.au.

Image courtesy of 123rf.com