What Ails the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments Beyond the DSSI?

One of the more significant tasks before the G20 countries is to find a lasting solution to the problem of external debt in developing countries, in particular low-income countries, whose vulnerabilities have exacerbated since the onset of the COVID-induced downturn. At the urgings of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors of the grouping took their first initiative to address the problem of debt vulnerabilities in low-income countries during their meeting in April 2020. They lent their support to the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in response to the significant increase in debt vulnerabilities and deteriorating outlook in many low-income countries arising from the pandemic.

The DSSI became effective in May 2020 and was initially designed to last until the end of the year. In November 2020, the G20 countries took two decisions: to extend the DSSI by another six months and to adopt a more structured medium-term framework, “Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI.” The DSSI was phased out in December 2021; therefore, the latter now exists as a framework for the debt redressal of low-income countries.

This paper critically examines the external debt amelioration strategy agreed to by the G20 countries. The paper argues that this initiative, like earlier initiatives on developing country debt, is unlikely to make a real difference to potential beneficiaries.

Debt Service Suspension Initiative

The DSSI, which became effective in May 2020, was a “time-bound suspension of debt service payments” for the poorest countries by “official bilateral creditors” until 2020. Countries eligible for this temporary suspension of debt service payments were those that were receiving loans from the soft-loan window of the World Bank, the International Development Association (IDA), as well as all least developed countries, that were “current” on any debt service to the IMF and the World Bank. Furthermore, the potential beneficiaries under DSSI were low-income countries eligible for support under the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF), the arm of the Fund that supports the world’s poorest countries. In total, 73 countries were potential beneficiaries of the DSSI (a full list of eligible countries is available here), who could be covered under the initiative, subject to requests made to suspend their debt service payments.

Under the terms of the DSSI, bilateral official creditors were expected to commit to suspending payments on all principals and interests that became due between May 1 and December 31, 2020, including all arrears from public sector borrowers. The repayment period was set at three years, with a one-year grace period. The G20 members agreed that creditors could extend the debt service suspension after considering a report by the World Bank and IMF on the liquidity needs of eligible countries. Private creditors were also invited to participate in the initiative on comparable terms.

The DSSI treated the debt problems of only low-income countries, and that too as a liquidity crisis. In other words, it was assumed that the debtors faced a short-term problem that could be resolved by injecting additional liquidity. In keeping with this understanding, low-income countries were extended temporary support until the end of 2020, even when it was quite evident that the pandemic-induced downturn would leave most of these countries in a precarious situation and that mere rescheduling of debt service payments would not be enough. Moreover, the G20 did not consider an important reality, namely, a significant number of developing countries were highly indebted and were at the brink of insolvency. Over the past decade, total long-term external debt owed by developing countries had more than doubled, from $4.3 trillion in 2010 to $9.3 trillion in 2021. Low-income countries were relatively worse performers, as their total long-term debt increased by 2.5 times during this period. Two indicators of debt vulnerability — the ratio of total long-term external debt to gross national income and the ratio of total long-term external debt to exports of goods, services, and primary income — help us understand the extent of debt vulnerability among developing countries. The former indicator shows that more than 81% of developing countries suffer from moderate to high levels of indebtedness, and 61% of these suffer from high levels of indebtedness. The latter indicator shows that 55% of developing countries suffer moderate to high levels of indebtedness. However, debt relief, albeit temporary, was extended solely to low-income countries.

Thus, the original framework of the G20’s DSSI suffers from at least three sets of weaknesses. First, it targeted only 73 low-income countries. Second, the framework aimed to simply shift the debt service burden of the beneficiary countries, treating the problem of external debt of these countries as one of solvency and ruling out the possibility that several affected countries were facing issues bordering insolvency. Third, the most significant problem with the DSSI was that private creditors were not mandatorily included. G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors agreed that “private creditors will be called upon publicly to participate in the initiative on comparable terms,” in other words, they would be “requested” to participate in the debt redressal initiative, as mentioned earlier.

The DSSI was applicable to 73 PRGF countries. However initially, 30 countries indicated that they would not join the initiative. Of these 30 non-participating countries, 23 firmly indicated that they were not interested in the initiative. However, five more countries subsequently participated in the DSSI. Thus, forty-eight countries participated in this initiative.

During the 19 months that it was in place, the DSSI suspended $12.9 billion in debt service payments owed by the participating countries to their creditors. Despite the G20’s request to private sector creditors to join the initiative, only one did, according to a brief published by the World Bank.

From DSSI to “Common Framework”

Weeks before the DSSI was to run its course, the Extraordinary G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting in November 2020 recognised that a somewhat longer-term view was necessary to redress the debt situation of low-income countries. This meeting had two sets of outcomes. First, the G20 members gave the DSSI a further lease of life beyond the end-2020 deadline that was agreed upon in their April 2020 meeting. The second and more substantive outcome was the adoption of the “Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI” (CF), which was also endorsed by the Paris Club of donors (https://clubdeparis.org/en/communications/page/historical-development).

With regard to the DSSI, a six-month extension of the DSSI was announced, which would enable debt relief to run until at least June 30, 2021. The G20 further agreed that by the 2021 Fund-Bank Spring meetings, the economic and financial situation of the beneficiaries would be examined to ascertain whether the DSSI had to be extended further by another six months.

CF was adopted to “facilitate timely and orderly debt treatment for DSSI-eligible countries, with broad creditors’ participation including the private sector.” To do so effectively, one of the key objectives of the CF was to bring together the Paris Club and non-Paris Club official creditors. The CF is intended to enable eligible countries to overcome not only their liquidity crises, which adversely affect their debt servicing capabilities, but also their solvency problems by providing debt relief consistent with the debtor’s spending needs and capacity to pay (IMF, Annual Report 2022:18). As in the case of DSSI, the procedures under CF can be initiated at the request of the debtor country.

Under the CF, the restructuring of debt is based on the IMF-World Bank’s Debt Sustainability Analysis and the collective assessment of the participating official creditors. The IMF has developed a formal framework for conducting public and external debt sustainability analyses, which, according to the Fund, is a tool for the better detection, prevention, and resolution of potential debt crises. The framework includes two complementary components: an analysis of the sustainability of total public debt and the total external debt of a country.

Debt-ridden country governments are required to adopt “medium-term policy frameworks that balance short-term needs and investments with medium-term fiscal sustainability.” Besides, they need to undertake reforms for “improving debt transparency and strengthen debt management policies and frameworks” which the Fund considers essential for reducing risks.[1] The restructuring of debt has to be consistent with the parameters of an upper credit tranche IMF-supported programme, whose conditionalities usually involve agreement with the Fund on a series of macroeconomic measures (including managing the budget) and other structural measures, such as discontinuation of petroleum product subsidies or reforming state-owned enterprises.

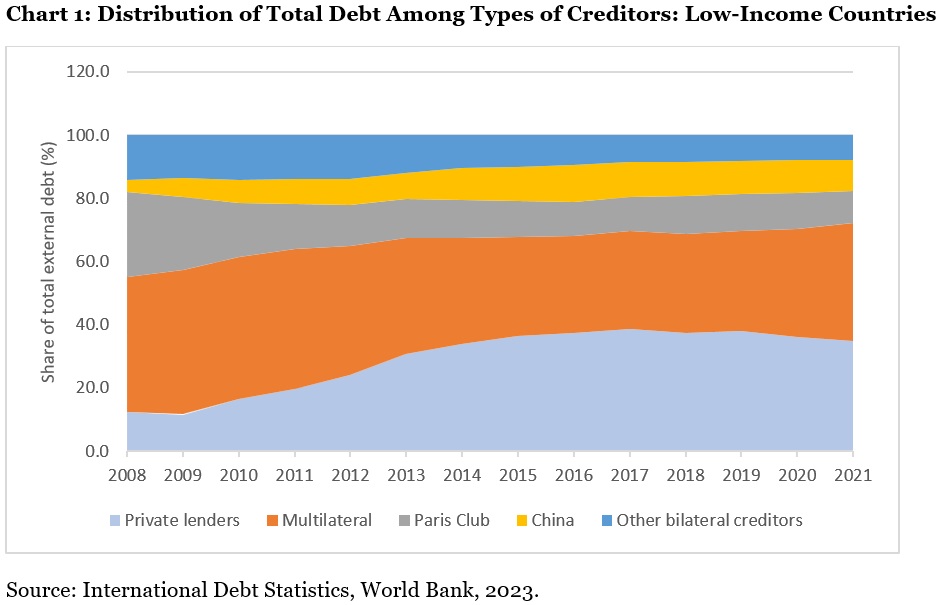

Private creditors have been the most formidable stumbling block for making CF effective, since private sector creditors held the largest share of claims in low-income countries as a whole between 2010 and 2021.

Coordination among Creditors

The CF requires all G20 and Paris Club creditors with claims on the debtor countries to coordinate their engagements with the debtor countries to finalize the key parameters of the debt treatment, in keeping with their national laws and internal procedures. The key parameters include: (i) changes in nominal debt service over the IMF programme period; (ii) debt reduction in net present value terms, where applicable; and (iii) extension of the duration of the treated claims. The key parameters will be established as to ensure fair burden sharing among all official bilateral creditors. Debt treatment by private creditors will be at least as favourable as that provided by official bilateral creditors. Finally, the G20 countries agreed that debt treatments would not generally involve debt write-off or cancellation, except when the IMF-World Bank debt sustainability analysis showed that write-off or cancellation was imperative.

The key parameters are recorded in a legally non-binding “Memorandum of Understanding” (MoU) signed by all participating creditors and the debtor country. Creditors have to implement the MoU through bilateral agreements signed with the debtor country. Therefore, CF allows official bilateral creditors to decide the extent of debt relief provided by all creditors. Debtor countries must then obtain comparable debt relief from private-sector creditors.

Low-income countries, in particular, and developing countries, in general, owe the largest share of their outstanding debts to private creditors (Charts 1 and 2), and CF could give rise to a situation wherein official bilateral creditors, which have a relatively small share of the claims, determine the debt relief that the private sector creditors should provide. Thus, debt restructuring under the CF could see a repeat of the earlier experiences of debt relief initiatives, including the IMF and World Bank-backed Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative launched in 1996.

Private creditors and multilateral institutions have not participated in the debt relief initiative “on comparable terms”. Further, there is every likelihood that the private creditors could undermine the principle of equitable burden-sharing by seeking more favourable terms from the debtors as compared to the other participating creditors. This raises the key point regarding the mechanisms that need to be put in place so that private sector creditors feel sufficiently incentivised to participate in debt relief initiatives.

The multilateral creditors, on the other hand, have not participated in debt relief initiatives, using their “preferred creditor status.” By doing so, these creditors are able to protect their favourable credit ratings and low market financing, which allows them to play their role as the international lender of last resort, providing cheap credit lines even during the worst crises.[2]

An Assessment of the CF

Since the CF was launched, only four countries – Chad, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Ghana – have requested the restructuring of their debts. This does not speak too well about the success of the initiative, especially due to the fact that the restructuring plan has gone through only in the case of Chad, and in the case of Ghana, the initial step, namely the establishment of the Creditor Committee, was established recently.[3] Thus, this initiative by the G20 countries to address the debt burden of low-income countries is turning out to be as ineffective as the earlier debt-reduction initiatives have been, since developing country debt crisis emerged as a vexed issue in the 1980s.

It is not difficult to understand that CF was doomed to be a failure due to several design flaws plaguing the initiative. First, the initiative is intended to “temporarily” suspend the debt service payments that the 73 PRGF-eligible low-income countries owe only to bilateral official creditors. This implies that the G20 countries did not want to include in the CF the debt servicing obligations of the targeted countries arising from the larger burden of debt that they owed to their private creditors as well as multilateral agencies. At the end of 2019, bilateral official creditors accounted for 25% of the total outstanding external debt stocks of developing countries, which had declined to 21% by the end of 2021. No country, except for Zambia, had publicly applied for similar treatment from private-sector creditors. Zambia asked for the rescheduling of $200 million worth of bond payments, but this request was refused. In this context, it must be mentioned that the debt that low-income countries owed to private sector creditors increased from just below $14 billion in 2010 to over $83 billion a decade later.

A second major flaw of CF is that it targets low-income countries, ignoring the significant problems with external debt that several middle-income countries, especially Sri Lanka and Pakistan, are struggling with. However, even for these countries, the mandate of the G20 initiative, namely, rescheduling debt service payments due to bilateral official agencies, would have done little to lessen the debt burden. For instance, in 2021, bilateral official donors accounted for 30.5% and 20.3% of the total outstanding external debt in Pakistan and Sri Lanka respectively.

Finally, it is important to understand the rationale of the CF, the “debt-relief” plan of the G20 countries. First, the initiative was intended to bring to the table “new donors” from the developing world, especially China and India, alongside the traditional “Paris Club” donors. This introduced a dynamic that the grouping has been unable to deal with, which encourages China and traditional donors to work together. The result is the usual blame game, which has resulted in an impasse. China has argued that it is not a Paris Club member and is therefore not expected to follow Paris Club-like policies. A more substantive point that the Chinese have made is the inclusion of private lenders.

China may be arguing for the inclusion of private lenders, but it should be obvious from the design of the CF that it is not intended to provide relief to debtors from the growing burden of external debt, but only to ensure that they remain solvent. This G20 initiative created a window to ensure that even in the face of severe economic stress following the onset of the pandemic, low-income countries were able to continue to meet their debt service obligations. The attempt was to avoid the sequence of events in the early 1980s, when several debt-stressed Latin American countries declared insolvency leading to the debt crisis, which eventually led to a “lost decade” for the indebted countries.

These issues arise because of a lack of full transparency regarding the amount of outstanding loans and their terms. Under CF terms, private sector lenders are expected to contribute data to the joint Institute of International Finance (IIF)/OECD Data Repository Portal. To this end, a multi-stakeholder Advisory Board on Debt Transparency has been established with three objectives: (i) to obtain perspectives on the scope and sequencing of the initiative; (ii) to assess challenges that arise and recommend solutions; and (iii) to provide a preliminary assessment of debt collection, data gaps, and implications of debt trends. Importantly, this OECD debt transparency initiative is a handmaiden of the G-7 countries, as the Advisory Board is overwhelmingly represented by members of the elite grouping and major financial institutions and investment funds, while being bereft of any representation from developing countries.

Conclusion

Thus, the “Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI” is yet another creditor-driven initiative aimed at protecting the interests of global capital, while the indebted countries remain condemned to bear the burden of debt. Importantly, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi flagged the threat of unsustainable debt facing some developing nations in his message before the First G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting organised under the Indian Presidency that concluded in February 2023. The meeting agreed to strengthen “multilateral coordination by official bilateral and private creditors” to address the “deteriorating debt situation and facilitate coordinated debt treatment for debt-distressed countries.” This was an unequivocal endorsement of the decision to suspend the debt service of the most vulnerable countries that the G20 countries had taken, especially in the Extraordinary G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting on November 13, 2020. The question is whether India can pull its political weight to alter the rules of the grossly inequitable debt management strategy of the G20 countries.

Notes and References

[1] IMF considers two areas of reforms are key. First, the adoption and implementation of a legal framework for the management of public debt that: (i) clearly defines public debt, debt instruments, and debt coverage; (ii) specifies the borrowing authority and the debt authorization cycle; (iii) clarifies the institutional arrangements of debt issuance, management, recording and reporting; (iii) discloses national debt strategies and borrowing; (iv) includes reporting, audit and accountability requirements and (v) regulates the consequences of non-compliance. Adequate requirements should apply also with respect to contingent liabilities. Second, debt management capacity needs skilled staff and the development of modern information technology systems for debt recording and management. (IMF. 2022. Making Debt Work for Development and Macroeconomic Stability, Box 3, pp.19-20).

[2] Essers, Dennis and Danny Cassimon. 2021. Towards HIPC 2.0? Lessons from past debt relief initiatives for addressing current debt problems, Working paper 2021.02, Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp, accessed from: https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/research-groups/iob/publications/working-papers/wp-2021/wp-202102/.

[3] Joint statement of the Creditor Committee for Ghana under the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI, May 12, 2023, accessed from: https://www.g20.org/en/media-resources/press-releases/may-2023/jscc/.

Biswajit Dhar is a former Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and presently a Distinguished Professor at Council for Social Development, New Delhi.

Image courtesy of 123rf.com