Understanding India’s Revamped FTA Strategy

After India took a decision not to join either mega-bloc, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) or the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a sudden reversal in India’s approach towards free trade agreements (FTAs) can be observed from early 2022 onwards. In a span of three months, between mid-February and the third week of May 2022, the Indian government signed two major trade agreements, one with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the other with Australia.

What led to the U-turn? Apparently, the US-China trade war, concerns related to cheap Chinese imports, attempts at reshoring “China-plus-one”[1] strategy, and geostrategic concerns may have compelled Indian policymakers to shift their approach to “Look West” from the much-hyped “Look East” policy of the previous regime. During the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) tenure, the Indian government agreed to explore an India-China FTA in 2007 and joined RCEP negotiations with China in 2011-12.

However, India gave the official reason for withdrawing from the RCEP that the agreement would have reduced import tariffs on goods by 80-90 percent. Industry experts feared this could lead to a flood of imports with a massive trade deficit. Apart from that, India had raised the issue of Most Favored Nation (MFN) obligations during the previous negotiations. This would have forced the Indian government to grant similar benefits to the RCEP nations that it previously granted to others. Additionally, India has claimed that the RCEP negotiations have failed to address its concerns. India sought fair agreement on the trade deficit and opening of services’ norms.[2]

The Renewed Interest

In addition to trade agreements with UAE and Australia, India has joined the US-initiated Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which was jointly launched by the US and other partner countries of the Indo-Pacific region on May 23, 2022 in Tokyo. The 14 IPEF partners represent 40 percent of the global GDP and 28 percent of global goods and services trade.[3] The 14 members of the IPEF are – Australia, Brunei, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, and the US. IPEF is structured around four pillars related to trade, supply chains, clean economy, and fair economy.

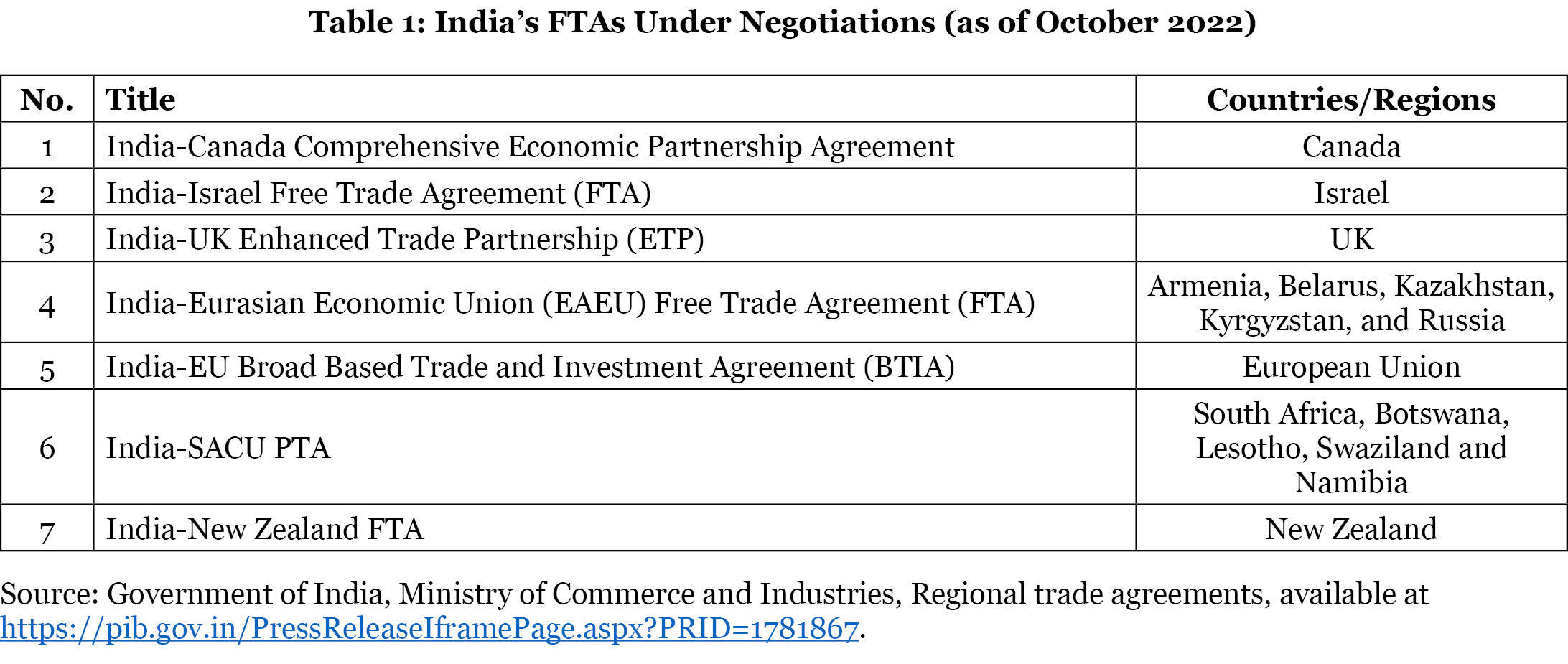

Furthermore, as on October 2022, India has been actively pursuing seven more FTAs (Table 1).

Among them, negotiations on the India-United Kingdom FTA, formally launched in January 2022, are currently accelerating with high-level meetings between the two prime ministers on the side-lines of the recent G20 summit in Indonesia.

The Shift

A quick analysis of tables 1, 2, and 3 reveals some interesting trends about India’s recent shift in FTA policy. It discerns three new trends.

First, it gives the impression that India is currently moving from the East and Southeast Asia region towards North America, the Pacific, Europe, Eurasia, Africa, and Central Asia. This could be one of the reasons why India did not join the ASEAN-centric RCEP but allied with the US-led IPEF. The US considers the geographic expanse of the Indo-Pacific stretching from its west coast to the western coast of India. This fits with India’s “Look West” policy.[4] The other recent initiative I2U2[5], which stands for India, Israel, the UAE, and the US (referred to as the “West Asian Quad”), is also part of India’s “Look West” policy.

Second, the targeted economies are relatively more developed than India.

Third, the focus is more on initiating bilateral agreements than multilateral ones.

The Rationale

A Free Trade Agreement (FTA) is a legally binding agreement between countries or regional blocs to reduce or eliminate trade barriers through mutual negotiations with the aim of enhancing cross-border trade of goods and services. However, nowadays, FTAs are much broader in scope and include disciplines on investment, intellectual property, competition, government procurement, and other policy areas. The WTO uses the nomenclature of Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) to describe FTAs. As per WTO statistics, as on November 7, 2022, there were 356 trade agreements in force.

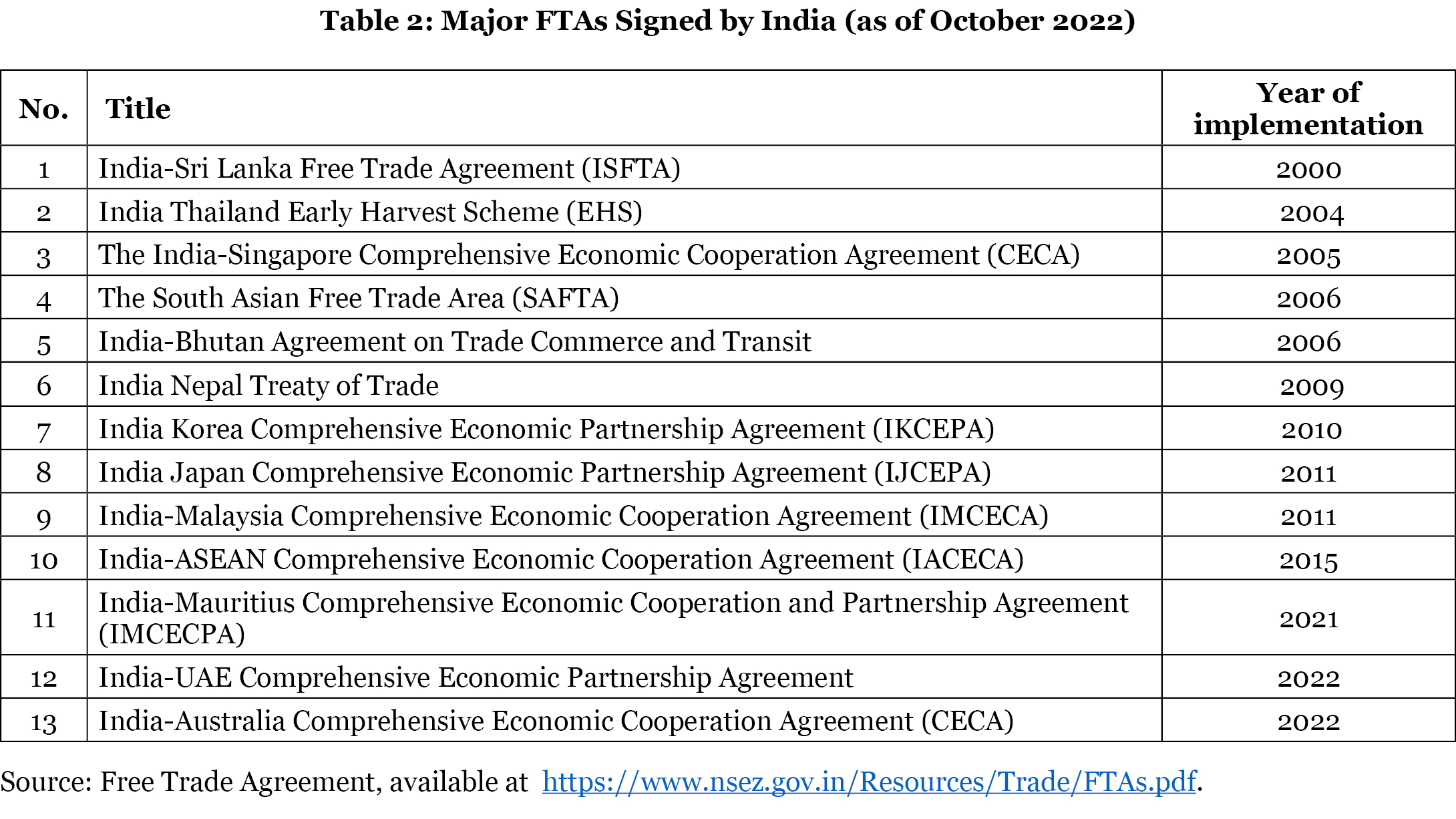

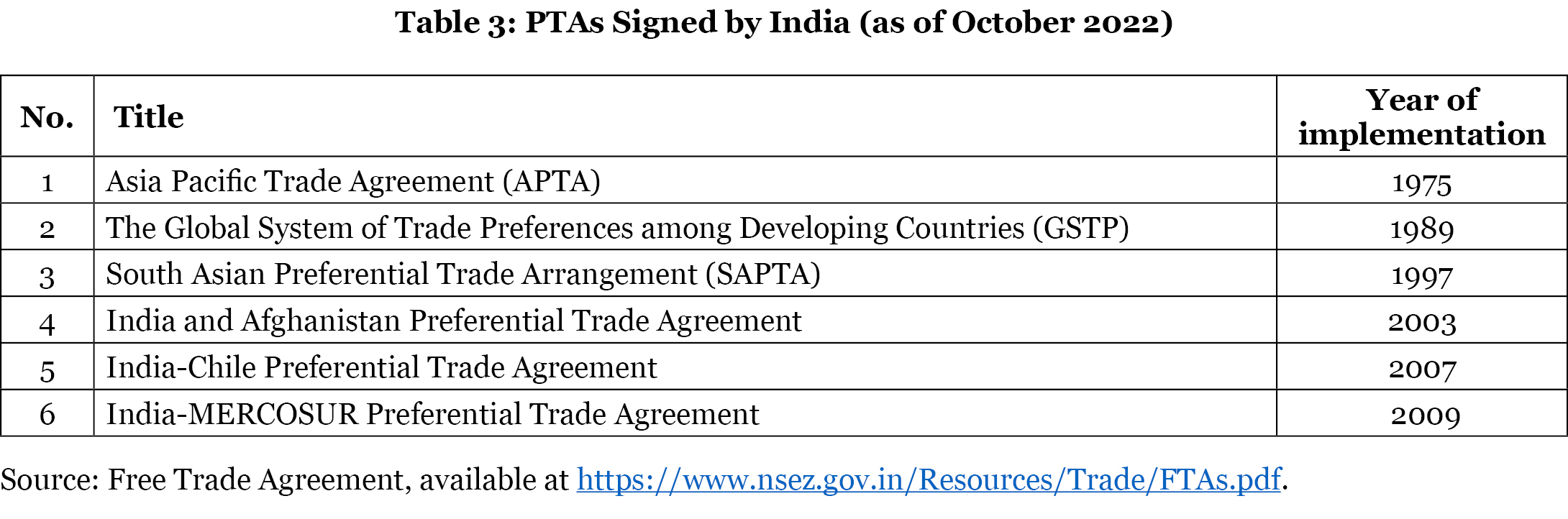

As of October 2022, India has signed 13 FTAs and 6 PTAs (see Tables 2 and 3). In the Indian context, the main differences between an FTA and a PTA are that the FTA is comprehensive in a number of areas and has deeper commitments, while a PTA is confined to trade in goods and only seeks tariff elimination in terms of a margin of preference (MOP). Moreover, the coverage of a PTA for goods is also limited compared to an FTA.

According to an official document[6] published by Noida Special Economic Zone, the primary drives for India’s FTA/PTA are following:

- Diversification and expansion of export markets

- Selectively cheaper access to raw materials, intermediate products and capital goods.

- Seeking opening in modes and sectors of India’s interest in services.

- Attracting foreign investment to stimulate manufacturing, generate employment and improve competitiveness.

- Geo political strategy such as “Act East” or QUAD resulting in FTAs with ASEAN, Japan and Korea and Australia.

FDI Inflow and Balance of Trade with FTA Partners

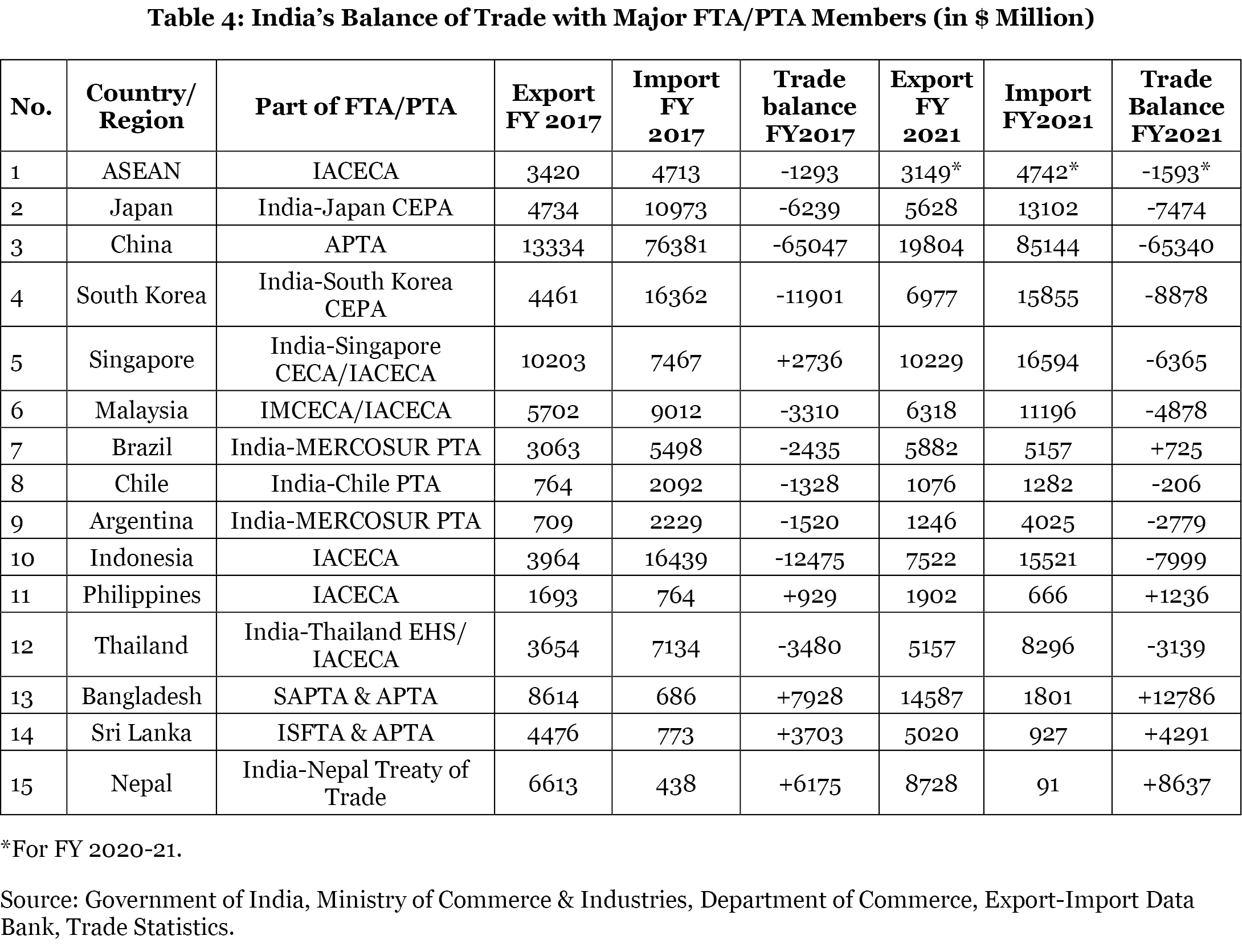

Table 4 shows that India has trade deficits with all other major trading partners, namely ASEAN, Japan, China, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Chile, Argentina, Indonesia, and Thailand, except for Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Philippines, and Brazil.

Although the trade agreement between India and China is limited only to their membership in the APTA PTA, (which was implemented in 1975), China’s trade with India is significant. In 2021, annual two-way trade crossed $100 billion for the first time and reached $125.6 bn, with India’s imports accounting for $97.5 bn, pegging the imbalance to nearly $70 bn.[7]

As per the FDI data maintained by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), the cumulative investment received from the first 11 countries/regions (listed in Table 2) was to the tune of $89.46 bn during the five years (between October 2016 and September 2021). However, it was impossible to ascertain if investment from a country had occurred due to the signing of a free trade agreement or for other reasons.[8]

A Clear Policy Needed

Ostensibly, India is following a hazy foreign trade policy with no clear direction. The confused stands India has taken while negotiating India-Australia Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (CECA), IPEF, India-EU Broad Based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA), and the India-UK Free Trade Agreement (FTA) are cases in point.

India-Australia CECA: On April 2, 2022, India and Australia signed a comprehensive interim free-trade agreement that will provide zero-duty exports to 100% tariff lines from India to the Australian market, benefiting labour-intensive sectors besides providing greater access to the services space. According to a press release by the Australian government, this agreement has “been built on strong security partnership and joint efforts in the Quad, which has created the opportunity for the economic relationship to advance to a new level, the press release claimed”.[9] Thus, the security aspect of the QUAD (also known as Asian NATO)[10], which had been revived to counter the Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific region, was one of the objectives of this trade initiative.

Indo-Pacific Economic Framework: The IPEF is structured around four pillars relating to trade, supply chains, clean economy, and fair economy. In September, India opted out of trade talks to avoid easing access to its markets via a multi-country deal, while moving ahead with the others in areas including supply chains, clean energy, and fair economy. It is reported that India opted out of the trade negotiation as a broader consensus has not emerged on certain issues like the environment, labour, and public procurement. But the US is positive to have all the IPEF pillars agreed to by November 2023, when the US hosts the annual meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.[11]

Briefing the media after the conclusion of the two-day IPEF ministerial meet in September 2022, Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said that India would continue to engage with the trade track in the IPEF and would wait for the final contours to be decided on the trade pillar before it formally associates with that track. When asked about the key areas of concern, he said digital trade, linkage of environment and labour to trade and possible binding commitments of any nature juxtaposed with the benefits that India will receive as a developing economy.[12]

India-EU Broad Based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA): On June 28, 2007, India and the EU began negotiations on a free trade agreement in Brussels, Belgium. The negotiations covered Trade in Goods, Trade in Services, Investment, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, Technical Barriers to Trade, Trade Remedies, Rules of Origin, Customs and Trade Facilitation, Competition, Trade Defence, Government Procurement, Dispute Settlement, Intellectual Property Rights & Geographical Indications, Sustainable Development. So far, 15 rounds of negotiations have been held alternately at Brussels and New Delhi.[13] The last meeting was held on May 13, 2013 in New Delhi. After that, the talks stalled due to differences on crucial issues. After a nine-year hiatus, both sides relaunched FTA negotiations in June 2022 and initiated separate negotiations for an Investment Protection Agreement and an Agreement on Geographical Indications.

The major sticking points were the EU’s demand for market access and higher levels of tariff concessions for automobiles, wines and spirits, as well as government procurement. Apart from that, the policies of India and the EU did not converge on issues such as intellectual property rights, data security, services, agricultural exports, chemicals, dairy and fisheries, registration of electronic products, and certification of telecom network elements. Many trade experts believe that India could have potentially gained in the services sector. But the issuing of work permits and visas is primarily the competence of the individual EU member states, so the EU cannot promise much. In addition, the EU had different qualifications and professional standards. Both factors made the trade deal less attractive to India.

One of the cornerstones of the EU’s trade strategy is trade and sustainable development, culminating in provisions on environment and labour standards in the trade agreement. It is argued that given the nature of businesses and the size of the MSME sector in India, a consultative negotiation approach may make sense. Making binding commitments on trade-related aspects of labor and the environment may not immediately produce the desired outcomes for India, particularly in terms of promoting inclusive growth and integrating MSMEs into global trade.[14]

India-UK FTA: Negotiations between India and the UK for a free trade agreement on an FTA were formally launched in January 2022.[15] The broad contours of the ongoing negotiations between India and the UK are not known. However, a draft proposal from the UK of the proposed FTA’s Chapter of Intellectual Property (IP) chapter was recently leaked by bilaterals.org. The leaked text (dated April 2022) shows that the UK has tabled harmful IP provisions that threaten to tighten the screws on producing, supplying, and exporting affordable generic medicines from India. The proposal contains harmful IP provisions that go beyond what is required by international trade rules through the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement).

According to Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), these “TRIPS-plus” provisions could undermine India’s robust pro-public health safeguards by requiring the country to amend its national IP and drug approval laws to introduce more monopolies on medicines. This, in turn, could have a detrimental effect on the sustainable production, registration, and supply of affordable, quality-assured generic medicines from India that millions of people worldwide rely on. MSF appealed to the UK and Indian governments to remove these proposals, including TRIPS-plus provisions, from the India-UK FTA negotiations.[16]

In its November 2022 briefing document entitled: “Damaging provisions for access to medicines in the leaked UK-India FTA negotiation text”, MSF has flagged its major concerns on the aggressive IP Proposals being negotiated in the proposed India-UK FTA and recommended Indian negotiators to press for the removal of IP from the scope of FTA negotiations. MSF has also called upon the UK government to withdraw the IP chapter and refrain from introducing ‘TRIPS-plus’ provisions in FTA negotiations that could impact the supply of lifesaving essential medical products.[17]

Concluding Observations

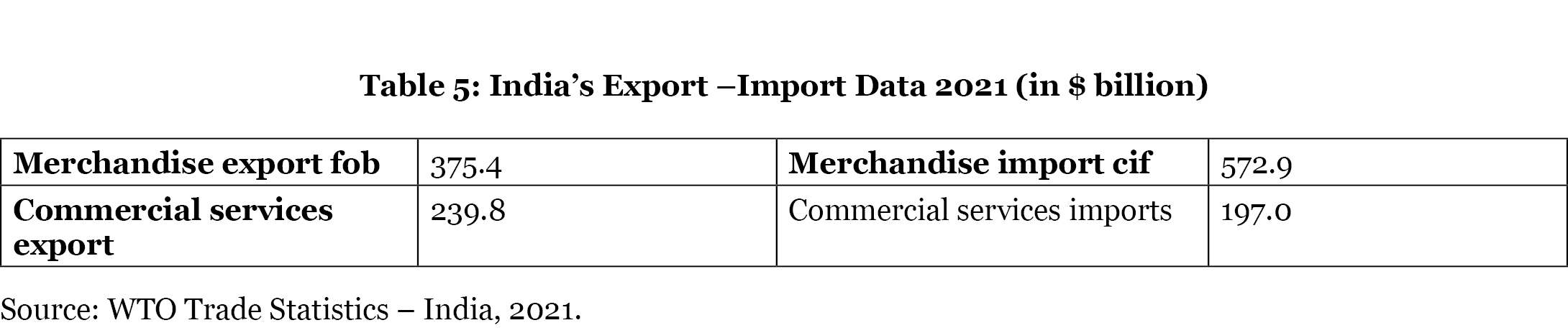

As evident in Table 5, India is a net exporter of commercial services, but in the merchandise sector, India is a net importer.

As per WTO Trade Statistics 2021, the five major export items (in terms of value US$ bn) of India were: (i) HS2710 (Petroleum oils, other than crude): $54 bn (ii) HS7102 (Diamonds, whether or not worked): $24.7 bn (iii) HS3004 (Medicaments in measured doses) $17.1 bn (iv) HS1006 (Rice): $9.6 bn (v) HS7113 (Articles and parts of jewellery): $10.5 bn.

The five major imports were: (i) HS2709 (Petroleum oils, crude): $106.4 bn (ii) HS7108 (Gold): $55.7 bn (iii) HS7102 (Diamonds, whether or not worked): $26.3 bn (iv) HS2701 (Coal; briquettes): $25.7 bn, (v) HS2711 (Petroleum gases): $24 bn.

What is worrisome is that India’s major merchandise export basket does not include high-end manufactured products. All major exported items, with the exception of rice, depend substantially on imported inputs. Almost total dependence on imported energy products (oil, coal, gas) has left India vulnerable to any global primary energy market crisis, leaving its manufacturing sector uncompetitive and risk-prone.

Until India finds a lasting solution to its energy needs and substantially reduces its dependency on imports for its main exports, no new free trade agreement will improve India’s competitiveness in the global marketplace. On the contrary, the unrestricted export of food items will endanger the food security of millions of its starving citizens, while liberal imports of agricultural products threaten farmers’ livelihoods.

Instead of focussing on FTAs with the developed countries/regions that are likely to insist on linking trade negotiations to binding labour and environmental standards, India may explore the possibility of strengthening the Global System of Trade Preferences (GSTP), among developing countries and enter into mutually beneficial long term trade relations with the member-countries of the G77[18].

Endnotes

[1] China-plus-one is a strategy whereby companies avoid investing solely in China and diversify their businesses towards alternative destinations.

[2] The Federal, Why is India off RCEP: Massive trade deficit, fear of excessive imports, November 23, 2020, available at https://thefederal.com/news/why-is-india-off-rcep-massive-trade-deficit-fear-of-excessive-imports/.

[3] Outlook, What Is Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) And Why India Has Opted Out Of Its Trade Pillar, September 10, 2022, available at https://www.outlookindia.com/business/what-is-indo-pacific-economic-framework-ipef-in-which-india-has-opted-out-of-its-trade-pillar-news-222446.

[4] Dipankar Dey, Gateway to prosperity, Millennium Post, July 2, 2022, available at https://www.millenniumpost.in/sundaypost/inland/gateway-to-prosperity-484338.

[5] The group’s first joint statement, released on July 14, 2022, states that the countries aim to cooperate on “joint investments and new initiatives in water, energy, transportation, space, health, and food security”, the joint statement is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/07/14/joint-statement-of-the-leaders-of-india-israel-united-arab-emirates-and-the-united-states-i2u2/.

[6] Free Trade Agreement (FTA), available at https://www.nsez.gov.in/Resources/Trade/FTAs.pdf.

[7] Ananth Krishnan, China’s total trade surplus with India ‘surpasses $1 trillion’, The Hindu, October 19, 2022, available at https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/chinas-total-trade-surplus-with-india-surpasses-1-trillion/article66031147.ece.

[8] Government of India, Ministry of Commerce and Industries, Regional trade agreements, PIB, December 15, 2021, available at https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1781867.

[9] Minister for Trade Tourism and Investment, Government of Australia, Historic trade deal with India, Media release, April 2, 2022, available at https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/dan-tehan/media-release/historic-trade-deal-india.

[10] Formally the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the Quad began as a loose partnership after the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, when the four countries joined together to provide humanitarian and disaster assistance to the affected region. It was formalized by former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007, but then fell dormant for nearly a decade, particularly amid Australian concerns that its participation in the group would irritate China. The group was resurrected in 2017, reflecting changing attitudes in the region toward China’s growing influence. The Quad leaders held their first formal summit in 2021. See The Hindu, What’s the 4-nation Quad, where did it come from?, available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/explained-whats-the-4-nation-quad-where-did-it-come-from/article65455882.ece.

[11] Eric Martin, India Opts Out of Trade Talks With US-Led Indo-Pacific Group, Bloomberg, September 12, 2022, available at https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/india-opts-out-of-trade-talks-with-us-led-indo-pacific-group-3336475.

[12] Press Trust of India, India Opts Out Of Indo-Pacific Economic Framework’s Trade Pillar As Broader Consensus Yet To Emerge Among Nations, Swarajya, September 10, 2022, available at https://swarajyamag.com/business/india-opts-out-of-indo-pacific-economic-frameworks-trade-pillar-as-broader-consensus-yet-to-emerge-among-nations.

[13] Government of India, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, India-EU Broad Based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA) negotiations, available at https://commerce.gov.in/international-trade-trade-agreements-indias-current-engagements-in-rtas/india-eu-broad-based-trade-and-investment-agreement-btia-negotiations/.

[14] Tanu M Goyal, India-EU FTA negotiations – how deep can we go?, The Economic Times, June 25, 2022, available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/trade/exports/insights/india-eu-fta-negotiations-how-deep-can-we-go/articleshow/92450413.cms?from=mdr.

[15] Geeta Mohan, PM Modi to meet UK PM Rishi Sunak on the sidelines of the G-20 Summit in Bali in Nov, Business Today, October 28, 2022, available at https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy/story/pm-modi-to-meet-uk-pm-rishi-sunak-on-the-sidelines-of-the-g-20-summit-in-bali-in-nov-351105-2022-10-28.

[16] Access Campaign, Briefing Document, Damaging provisions for access to medicines in the leaked UK-India FTA negotiation text, November 2022, available at https://msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/2022-11/IP_UK-India%20FTA_Factsheet_Final_ENG_2.11.2022.pdf.

[17] Ibid.

[18] The Group of 77 is the largest intergovernmental organization of developing countries in the United Nations, which provides the means for the countries of the South to articulate and promote their collective economic interests and enhance their joint negotiating capacity on all major international economic issues within the United Nations system, and promote South-South cooperation for development. For details, see https://www.g77.org/doc/.

Dipankar Dey is a faculty member at Techno India School of Management Studies, Kolkata. Views expressed here are personal.

Image courtesy of 123rf.com