Why the IFF is Unlikely to Help Poor Countries with Debt Relief

UN Secretary-General António Guterres and world leaders sounded the alarm on debt payments recently at a high-level meeting on debt and liquidity. There are too many high debt payments diverting money needed by poorer countries to tackle the pandemic and its economic downturn, climate change, and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs). In April 2020, the G20 offered ways and conditions to the poorest countries for suspending servicing their debt during the pandemic by launching the Debt Servicing Suspension Initiative or DSSI. Since many poor countries’ debts are increasingly owed to private creditors, the G20 had “call[ed] on private creditors, working through the Institute of International Finance (IIF), to participate in the [DSSI] on comparable terms” to those of the public creditors and on a voluntary basis. The G20 then worked closely with the Institute of International Finance.

However, when meeting on October 14, 2020, the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors stated that they were “disappointed by the absence of progress of private creditors’ participation in the DSSI”. Indeed, a significant portion of the money that was freed up, granted or lent, went to servicing debt to private creditors such as banks and bondholders. For instance, IMF Covid-19 loans in 2020 to the poorest countries amounted to US$42.9 billion, but 47.3% was used to pay private creditors. In other words, the private creditors through the IIF had not delivered, and payment to private creditors continues.

At their meeting of April 7, 2021, the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors agreed on a final extension of the DSSI by six months through the end-December 2021.

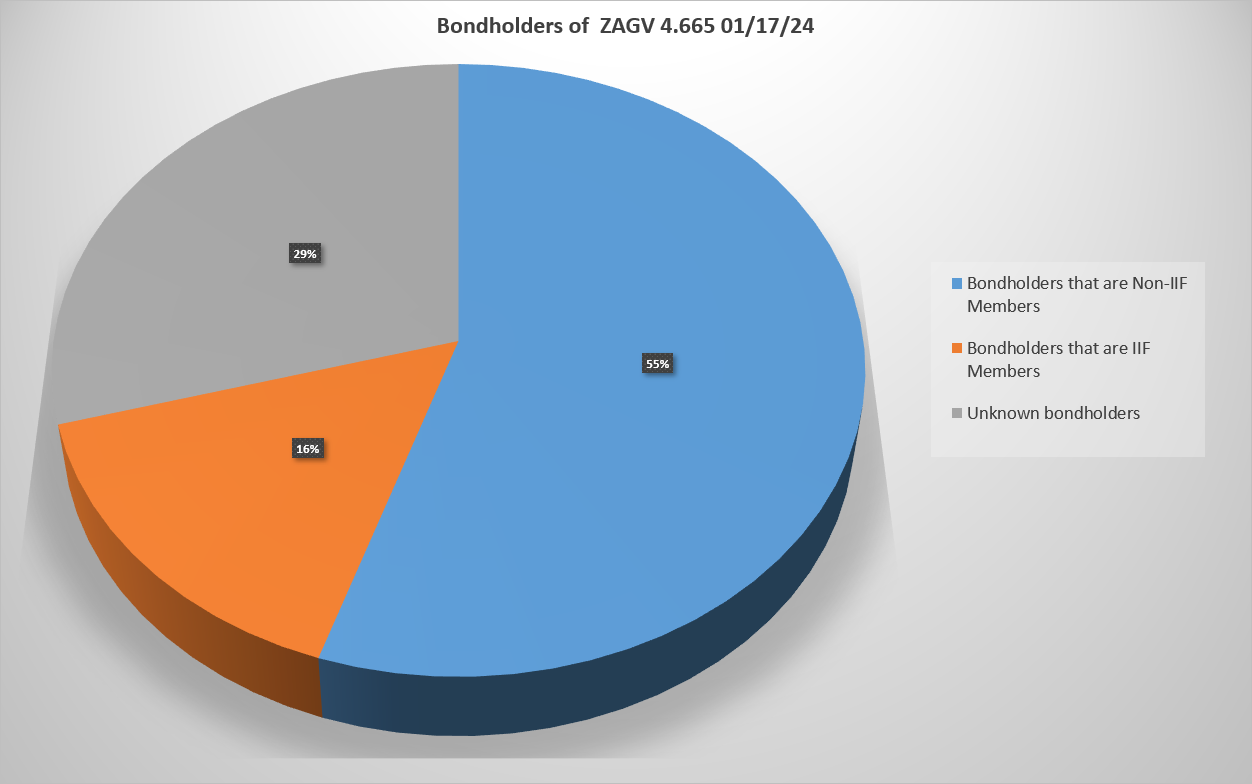

What is the Institute of International Finance, and why was it given a privileged role in the G20 debt initiative? At SOMO, we have started to research the IIF’s role and influence. The IIF is the largest global industry association and lobby club of the private financial industry. Its members cover all private debt market activities, such as the banks providing loans (including Chinese banks), investment banks underwriting bonds, credit rating agencies rating loans and bonds, and institutional investors and fund managers who are buying the bonds. Still, many private creditors of developing countries are not members of the IIF, as illustrated with research into a bond of the heavily indebted South Africa (graph 1).

Graph 1: Holders of the South Africa bond that expires in 2024

Non-IIF members holding more than 1% of the bond: Fuh Hwa Securities Investment Trust Co Ltd (47.5%), Schroder Investment Management (Taiwan) Limited (1.7%) and Prescient Investment Management Pty Ltd (1.0%); Affiliates of IIF members holding more than 1% of the bond: BlackRock subsidiaries (3%), TIAA Global Asset Management (2.1%), RBC Global Asset Management Inc (1.7%), Metropolitan Life Insurance Co (US) (1.4%). Source: Refinitiv (downloaded March 26, 2021) and SOMO research.

The IIF was called upon by the G20 because, for decades, it has sponsored various voluntary and market-friendly instruments to deal with developing country debt. Through the “Principles for stable capital flow and fair debt restructuring”, the IIF promoted transparency, cooperation, good faith, and fair treatment between borrowing governments and private creditors. Although the IIF runs the secretariat of the Principles’ Group of Trustees and Consultative Group, its members have no obligation to apply the Principles. The IIF’s comparative advantage comes from its membership and the many databases and briefings on debt. That information is mostly not accessible to the public and governments, which is at odds with the IIF’s Voluntary Principles for Debt Transparency.

The IIF and its member committees specialized in public debt have been actively discussing the DSSI with the G20, the Paris Club, public creditors, non-IIF members, and debtor countries. The IIF responded in May 2020 by designing its own “IIF Terms of Reference of Voluntary Private Sector Participation in the G20/Paris Club DSSI”. In July, the IIF issued a “Template Waiver Letter Agreement” to avoid lower credit ratings stopping countries’ participation in the DSSI. Nevertheless, these new IIF instruments seem not to have affected debt negotiations at the national level, such as during Zambia’s crisis after it defaulted on its debt. An analysis of the Zambian bond that expires in 2022 reveals that some known bondholders were IIF members who could have promoted and used the IIF instruments.

Graph 2: Holders of a Zambia bond that expires in 2022

Affiliates of IIF members holding 1% or more of the bond, as known on March 26, 2021: Amundi subsidiaries (5.5%), UBS Asset Management (2%), PIMCO (1.3%), INVESCO Asset Management Limited (1.2%), JPMorgan Asset Management UK Limited (1%), Finisterre Capital LLP (1%). Source: Refinitiv (downloaded March 26, 2021) and SOMO research.

The experience of the past year has exposed several problems that need to be addressed immediately. First, the IIF interpreted its role to the G20 as “the principal point of contact, knowledge partner and clearinghouse to generate private sector feedback and support.” That role is questionable, given that many of its members had no interest in reducing debt payments at the debtor country level. Besides, many bondholders are not members of the IIF.

Second, the voluntary G20 approach towards the private creditors and the IIF voluntary instruments did not result in much-needed debt relief. All official proposals like those at the UN’s high level have failed to solve private creditors’ problems to avoid a major global debt crisis.

Myriam Vander Stichele is a senior researcher with the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO), Amsterdam.

Image courtesy of IIF